Martin Newman explores a relatively undiscovered Balkan nation that’s going up in all departments. We are publishing the full article that Martin wrote about Serbia.

The minibus ground to a halt at the top of a steeply treacherous incline. “The driver won’t go any further,” our guide Djina told us, turning in her seat. “It’s on foot from here.”

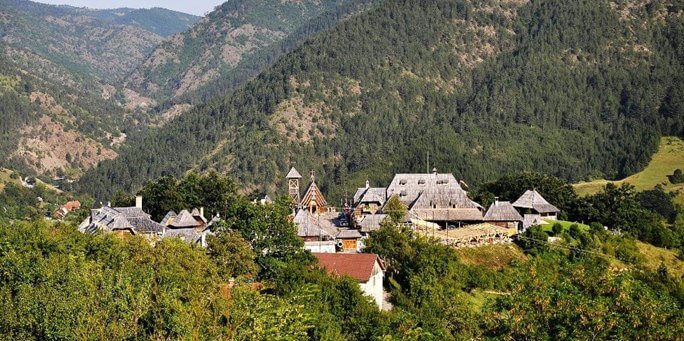

Somewhere in the valley deep below us was the Pustinja Monastery, with its 17th-century chapel.

Hidden from view to anyone driving in Serbia’s western mountains and barely signposted, it is as close to the definition of “sanctuary” as you can find.

We clambered several hundred yards down the stony dirt track until we reached a flat area by the river, in which stood a group of buildings surrounded by a wall. A large wooden gate with a hefty iron knocker blocked us from passing.

We clambered several hundred yards down the stony dirt track until we reached a flat area by the river, in which stood a group of buildings surrounded by a wall. A large wooden gate with a hefty iron knocker blocked us from passing.

In the pristine silence I lifted the great clump of metal and slammed it down thrice.

The sound resonated like a gong through the valley.

Birds shrieked and leapt skyward, the undergrowth clamoured with startled critters and from behind a wall a small, angry nun in a beekeeper’s outfit burst forth directing a rake and a shrill stream of wild invective at me.

Apparently, the door was unlocked.

“Sorry,” I said. Then remembering the Serbian, with a smile: “Izvinite!”

The stooped old woman spat in annoyance and shook the rake one more time before returning to her hives.

Built in 1622 on the ruins of an 11th-century monastery, the chapel, with its Byzantine-inspired frescoes, is typical of the many Unesco cultural sites and unspoilt natural beauty spots in Serbia that have remained largely hidden from Western tourists.

A nation disrupted by war throughout centuries of existence, it is one that has rebuilt and readjusted to conflict time and again.

But while grappling with the post-communist, ethnically divided break-up of Yugoslavia, economic deprivation and exclusion from the EU, Serbia’s many assets have been largely overlooked.

Tour group driver Bojan, a retired air force pilot, had brought us from Belgrade to take in the western ranges and, with rain chasing us to the top of the country’s border with Bosnia, we reached the River Drina for a rafting excursion at Bajina Basta, which holds an annual boozy regatta (of sorts).

It is also known for the fisherman’s house built on a rock in the middle of the river. As a tourist attraction, the House on the Rock is a source of some pride in these parts but, as with most things that I discovered in Serbia, it is the stuff the Serbs take for granted that is often more rewarding for visitors.

From lush green pastures dotted with farmhouses along the river, we drove into the mountains and the Tara National Park, dark and dense with pines, home to brown bears and crystal-clear springs and rivers.

From lush green pastures dotted with farmhouses along the river, we drove into the mountains and the Tara National Park, dark and dense with pines, home to brown bears and crystal-clear springs and rivers.

Along the way we filled up at roadside restaurants. Throughout Serbia, the national cuisine centres on grilled meats and fish, and the Serbs are high on hospitality, so wherever we went the food was delivered in abundance.

Our table was piled high with freshly prepared, mostly local farm-raised produce and included wonderful breads and salads in among the never-ending parade of charcoal-cooked meats.

Chief among these delights was cevapcici, a stick of minced meat, which is like a Greek kofta. In Serbia the notion of organic food is a bit of a non sequitur, as the traditional agriculture sector is almost entirely organic, by British standards anyway.

Continuing our climb into the mountains, we stopped several times to trek along trails marked with limestone outcrops, the spongy forest floor undisturbed by man. These rambles yielded impressive views, looking down through the fog-shrouded upper air into lake-filled valleys below.

Our first night was spent in very comfortable alpine lodges high in the Zlatibor region, where our hosts fortified us with the national drink rakija, a plum brandy that would stun an elephant.

In the morning we took the narrow-gauge steam railway Sargan Eight through the mountains to the wooden village of Drvengrad, constructed mostly to traditional building techniques by Palme d’Or winning Serbian film director Emir Kusturica.

In the morning we took the narrow-gauge steam railway Sargan Eight through the mountains to the wooden village of Drvengrad, constructed mostly to traditional building techniques by Palme d’Or winning Serbian film director Emir Kusturica.

The director of Underground, he began constructing the ethno village in Mokra Gora in 2003, while shooting his film Life is a Miracle. The village is designed as a showcase of folk architecture.

Next we headed to the nearby Tornik peak, one of many ski destinations in winter. In pre-season they do a roaring trade in mountain biking and tubing, so we took a ski lift to the 4,900ft top run. With an approved guide leading the way, we were given a helmet and bikes with highly shock-absorbent wheels.

They say once you learn to ride a bike the skill is always with you.

What they don’t say is riding a BMX as a kid, then taking a 25-year sabbatical before getting astride a high-seated trail bike with brakes that throw you over the handlebars at the slightest twitch, is really bloody frightening.

I spent about 20 minutes cajoling my cycle like an untamed bush mare before careering precariously down the trail as though I was atop a Penny Farthing.

Having survived the bikes and the nightclubs of Zlatibor, we left the mountains behind us and headed back to the capital to experience the nightlife there.

Belgrade, a city of 1.7million (This figure was corrected after publication) people, is divided between the old-style centre and the more modern suburbs that have grown up around it. Full of beautiful apartment blocks, museums and churches, it also contains the influence of Tito’s communism.

Belgrade, a city of 1.7million (This figure was corrected after publication) people, is divided between the old-style centre and the more modern suburbs that have grown up around it. Full of beautiful apartment blocks, museums and churches, it also contains the influence of Tito’s communism.

Built on the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, it offers much in the way of beautiful scenery and you must definitely try a meal on one of the multitude of floating restaurants along the banks of the Sava.

If you like your sightseeing, there are some must-dos in Belgrade that include the magnificent St Sava church and the Kalemegdan fortress.

There are also Roman ruins to explore and the House of Flowers mausoleum of Tito.

Belgrade’s buildings, many of them decaying through years of neglect, have a rustic charm, but in among them reside some of the more chic and modern bars, restaurants, nightclubs and clothing stores in Europe.

I have visited Belgrade before and am always struck by how fashionable Belgraders are, despite the average monthly wage being just £330.

In fact food and fashion are high on the agenda here. Ensconced in the five-star Metropole Palace Hotel, I found they had the best breakfast buffet, which included everything you’ve ever seen plus a huge range of cakes and sweets – reflecting the influence of the Ottoman Empire.

We spent our evenings at Public Dine & Wine, which is a tastefully contemporary restaurant in the bohemian district of Skadarlija, and at Reka on the Danube, where we danced the night away and I learnt one of the great Balkan dance moves. Wonderful in its simplicity, it involves pointing above your head indiscriminately while looking thoughtful or a little emotional (especially good during one of the rousing turbo folk ballads that are popular here).

As a city, it is a fully formed destination, brimming with great things to see and do, as well as places to eat and to party in.

And outside of the city, there are many signs of a gentle awakening in tourism as Serbia embraces its natural treasures and the durable friendliness of its people.

Source: www.mirror.co.uk